Studies using qualitative methodology:

CAT Qualitative Research Overview

Dr Evelyn Gibson

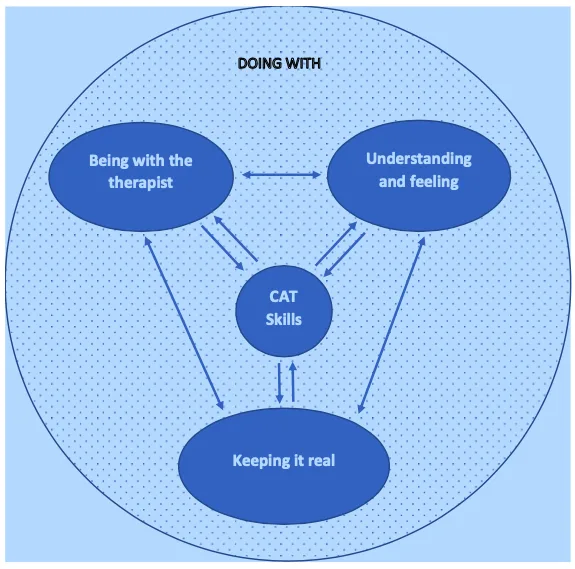

Rayner (2005) used grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Corbin & Strauss, 1990) to understand change in cognitive analytic therapy (CAT) and used this information to develop a model of CAT (see Figure 1)

Figure 1: Rayner’s (2005) model of CAT

“Doing With” conceptualises the working bond between client and therapist in CAT. All participants recognised that they needed to take responsibility for change; however, despite this, some participants were wary of how dependent they felt they were becoming on therapy and the therapist. The theme of “Being with the Therapist” conceptualises the importance clients placed on the qualities of, and their relationship with, the therapist. Participants stressed how important it was to feel understood; listened to; valued; and, to have a trusting relationship with their therapist. Therapist actions that participants described as being pertinent to change were challenging unhelpful thoughts; explaining and recognising patterns; questioning; and, helping clients to think for themselves. Change was implicit on developing insight, recognising behaviour and making attempts to do things differently. Accessing and exploring childhood experiences was a key feature in beginning to understand the origins and development of behaviours. Most people reported general positive changes and not specific symptom relief and attributed these changes to therapy e.g., learning to be kind to oneself; reducing self-criticism; improving self-confidence; self-esteem; and, assertiveness. Participants acknowledged the fragility of change and felt that it was an ongoing and continuous process. The theme of “Keeping it Real” represents the importance of “doing” and not just talking in therapy. Participants also found continuity between sessions valuable, and metaphors and techniques helped to keep things grounded. The majority of participants found the time limited structure comforting and useful; however, one person found it frustrating and rigid. Feelings about the structure seemed to influence emotional reactions towards ending therapy. Those who found the structure useful were more accepting of the ending; however, when it was experienced as restricting, this led to feelings of dread, fear and anger.

In a later study, Rayner, Thompson and Walsh (2011) expanded on these findings. Their results indicated that the experience of CAT is characterised by a strong feeling of actively working together with the therapist. The emergent themes were inter-related. Changes were facilitated by being in a collaborative trusting relationship with the therapist where the client felt understood and safe to explore deep emotional and painful issues. Keeping the therapy real by using real situations allowed clients to feel they were actively doing something to achieve change. It was highlighted that, individuals who had the greatest emotional reactions to the letters and diagrams and took an active role in constructing them appeared to gain most benefit from them. Participants described therapy as a painful emotional experience. Participants’ sense of accepting this as a “necessary evil” to gain maximum benefit from therapy is in line with Saunders’ (1999) findings that clients’ affective experience has a strong relationship with treatment effectiveness. Furthermore, it supports the notion that cognitive insight alone may not be sufficient to instigate change but that affective arousal is also needed (Watson & Rennie, 1994). The changes participants attributed to therapy were more general shifts in their experience of, and relationship with, themselves. This study has demonstrated that such fundamental changes within the structure of self can be achieved within a time limited therapy.

In a study of clients’ experience of engaging in CAT, Tzouramanis and colleagues (2010) highlighted that clients found a number of aspects helpful: having a new understanding; self-monitoring; CAT being time-limited; and, the relationship with the therapist.

Evans, Kellett, Heyland, Hall and Majid (2016) conducted a pilot RCT with the primary aim of investigating the use of CAT for bipolar disorder. As part of this, a thematic analysis was conducted on clients’ qualitative descriptions of helpful events named on the Helpful Aspects of Therapy questionnaire (HAT; Llewelyn, 1988). The HAT prompts clients to identify, describe and rate the most helpful event of each therapy session. The themes identified were then compared according to the different phases of CAT (i.e., reformulation, recognition and revision stages). The results identified seven themes: 1) recognition of mood variability; 2) the experience of narrative feedback; 3) the use of reformulations; 4) identifying exits; 5) psychotherapeutic support; 6) recognition of progress; and, 7) uneventful sessions. The latter were infrequent regardless of the phase of CAT. During the reformulation stage, the most commonly occurring helpful event was recognising patterns in mood variability. This continued to be a common helpful event across recognition and revision phases. Co- construction of SDRs was identified as the most useful aspect during the reformulation phase. During the recognition stage of CAT, the most frequent helpful events were being able to recognise the progress made in therapy and starting to generate exits.

Taylor and colleagues (2019) looked at the experience of receiving CAT for psychosis. They developed the following themes:

- 1) Gaining Insight into Experience of Psychosis – This encompassed developing insight into what triggers psychosis; how paranoia relates to past experiences; and, how psychosis relates more broadly to thoughts and emotions. Furthermore, it involved understanding the relationship between thoughts; beliefs; emotions; and, actions.

- 2) Building a Therapeutic Relationship referred to the active role of both participants and therapists. Clients valued being listened to and this enabled them to let their guard down and to overcome feelings of embarrassment. Sharing history was described as tough but helpful. The trust built allowed therapist and clients to explore the possibility of different perspectives on problems.

- 3) The Usefulness of CAT tools highlighted how different tools were “validating tangible objects” and provided evidence of being listened to. Clients described the value of seeing the work of therapy written down and described receiving a letter as being emotional and personal.

- 4) Making Positive Changes focuses on the changes participants associated with CAT (e.g., being empowered to talk; better relationships; and, increased control and confidence.

Kellett and Stockton (2021) evaluated the experience of eight sessions of CAT for obsessive morbid jealousy using the Change Interview (CI). The CI is a 60 – 90 min semi-structured interview conducted after therapy has been completed which assesses whether change has occurred during a therapy; whether any changes were associated with the therapy; and, specifies what these changes were. The participant gave a positive account of therapy and reported that CAT had been helpful in eight different ways (understanding why; understanding consequences; reduced instigation of arguments; being happier; individuation; grieving; and, reduced checking). Changes were generally rated as unexpected; important; and, unlikely to have occurred without therapy.

Balmain, Melia, John, Dent and Smith (2021) explored the experience of service users with complex mental health difficulties who engaged in a full course of CAT therapy. The research identified three themes: changes due to CAT; evocation and exposure to negative emotions; and, the process. Changes due to CAT referred to personal gains experienced by clients e.g., improvements in emotional regulation and stabilisation; self-worth; and, interpersonal functioning. Individuals described enhanced understanding of their past experiences; current triggers; and, unhelpful patterns through use of CAT tools. Exposure to negative emotions referred to the strong emotions elicited during therapy. Sadness was the most dominant emotion evoked in therapy. This was related to increased insight into “patterns” and the experiences that underpinned their development. In terms of the process, it was identified that specific CAT tools enabled clients to feel understood and accepted by their therapist. Some service users felt that they needed more time and would have valued follow-up sessions after therapy had ended.

CAT Tools

Reformulation

Evans and Parry (1996) investigated the impact of the process of reformulation. They reported that reformulation was viewed as impactful by clients even though it did not affect session-by-session measures of perceived helpfulness; therapeutic alliance; or, individual problems. Shine and Westacott (2010) expanded upon these findings by investigating the impact of reformulation for clients with less severe mental health difficulties. Their results were similar to those reported by Evans and Parry (1996) in that there was no immediate significant impact of the reformulation session on outcome measures of therapeutic alliance; however, elements of the reformulation process may have impacted upon the clients outside of the reformulation session and, as such, had a more cumulative, longitudinal impact. Stockton (2012) also found that narrative reformulation did not improve the working alliance between the therapist and service user or the helpfulness of the therapy.

Rayner et al. (2011) highlighted that, individuals who had the greatest emotional reactions to the letters and diagrams and took an active role in constructing them appeared to gain most benefit from them. Tyrer and Masterson (2019) studied the change process in CAT for common psychological difficulties. Changes that were identified as having occurred over the course of therapy were“accepting feelings”; “being less critical of self”; and, “being less overwhelmed by worry”. All these changes were rated as important and were attributed directly to the experience of therapy. Furthermore, reformulation tools were helpful in enabling clients to recognise patterns. Taplin (2015) found that reformulation helped clients to understand themselves and make sense of their experiences. Reformulations were described as a method for change and as a tool used both inside and outside of the sessions. There were mixed experiences regarding the impact that the SDR had on the service users’ relationship with their therapist. Chadwick, Williams and MacKenzie (2003) reported that service users described a negative emotional reaction when having a formulation shared with them when receiving CAT.

Jefferis, Fantarrow and Johnston (2020) aimed to generate a model of processes involved in the early stages of CAT mapping from the therapists’ perspectives. Therapists read a referral letter for a fictional client and then took part in a role-play of a first therapy session with an actor playing the role of the client. Based on the outcomes of interviews following the roleplay, a conceptual model depicting the processes involved in CAT reformulation diagram construction was developed (see Figure 2). The Torchlight model of CAT mapping aimed to capture the interactive and relational processes which emerged.

Figure 2: The Torchlight Model of CAT (Jefferis, Fantarrow and Johnston, 2020)

The three overarching contributory concepts to mapping were the client, the therapist and CAT. Each has a particular quality, but when mixed, they produced something unique and different (in the metaphor, a different coloured light). When all three come together, they illuminate a process of mapping which is more than the sum of those individual elements. The central category of “Making the CAT Map” describes the tasks involved in starting to construct a CAT diagram using a series of fluid but connected tasks: information gathering and forming hypotheses; getting a good enough understanding; reviewing and adding. Therapists described reaching a point of “bringing it all together” to condense the diagrams into one integrated map. This was still noted as a process of development rather than conclusion. “Collaboration” describes the collaborative context for the mapping tasks and involved actively seeking to capture the client’s ideas; developing a shared language; and, to be in dialogue. Collaboration was seen as increasing over time. An overarching concept, but one which particularly relates to collaboration, is the attention to the client’s zone of proximal development (ZPD), both cognitively and affectively (i.e., working with the client at their current level of capability and trying to extend it). The unique contribution brought by each individual client is also important. This includes the nature of the presenting problems and therapists’ tentative awareness of clients’ procedures. Additionally, clients own learning style, sensory and literacy issues and diversity may have an influence on how mapping is approached. CAT’s conceptual framework coloured all the processes, including how therapists structured both the content and process of mapping.

Therapeutic Letters

CAT theory proposes that therapeutic letters (TLs) can facilitate self-awareness by helping to make sense of previously confusing life experiences through the use of narratives. Hamill, Ried and Reynolds (2008) investigated how TLs impacted on CAT therapy from the perspective of the client. In this study, all participants described the letters as helping to create awareness of self; to recognise the strength of the therapeutic relationship; and, a to develop deeper understanding of therapeutic processes. The letters framed the therapy, offering meaning; comfort; direction; and, sense of progress over time. Alongside these positives, another theme was that of risk including decisions of whether or not to reread them and risk exposure to painful content; whether to share them with others; and facing their thoughts and feelings about termination and their relationship with the therapist while trying to write their own good-bye letter. At the same time, letters provided clients with some control over painful internal processes. All participants identified that one important feature of the letters was their permanence. TLs have been described as transitional phenomena (Ingrassia, 2003; Howlett & Guthrie, 2001) and the results of this study suggested that the letters helped some clients to develop a sense of object constancy regarding the therapist and the containing process of therapy, thus becoming a “transitional object” in the development of a strong, internalised attachment figure (Winnicott, 1953). Similarly, the transitional quality of the good-bye letters may have buffered the difficult emotions evoked in managing separation from their therapist.

A number of qualitative studies have explored the effects of receiving TLs during psychological therapy in general. Four broad themes emerged from these: 1) making connections; 2) extending the work of therapy; 3) managing endings; and, 4) negative impacts. “Making Connections” refers to the feeling of being connected with others through TLs. This includes enabling clients to share the work of therapy with others (Howlett & Guthrie, 2001) and the impact of TLs on the therapeutic alliance. Pyle (2006, 2009) identified the theme “Curiosity and Connection” to describe the client’s inquisitive reading of TLs and how this had a positive impact on their relationship with the therapist. Clients described the “Consolidation” effects of TL on therapeutic relationships, by providing tangible evidence of the clinician’s commitment and care. Client experiences of “Feeling Known and Valued” by the clinician were also identified by Freed et al. (2010). Rayner et al. (2011) found that reformulation letters were described as contributing to the structure and professionalism of therapy. Goodbye letters had less impact and were primarily perceived as documenting progress.

Reformulation letters were credited with initiating the process of change and were described as providing a new perspective and enhanced self-empathy. Post-therapy, reformulation letters were described as providing a record of prior functioning; a marker of progress; and, maintaining connection with the therapist. Moules’ (2003) highlighted that the relationship between TLs and therapeutic alliance is interactive and had the potential to enhance healing or promote separation. There is the potential for TLs to be misinterpreted without the possibility for immediate correction in therapeutic conversations.

“Extending the Work of Therapy” refers to TLs extending therapy by protecting and conserving therapeutic narratives, so that they remain available to the client after therapy ends. Both Guthrie (2001) and Pyle (2009) proposed that TLs provide a template for the ongoing assimilation of problematic experiences. In addition, TLs may also function to promote wellbeing (Freed et al., 2010; Howlett & Guthrie, 2001; Pyle, 2009).

TLs are often seen as “Managing Endings” by being a tangible transitional (Howlett & Guthrie, 2001); precious (Freed et al., 2010); and, perpetual object (Pyle, 2006, 2009). The tangible nature of TLs was described as allowing for the therapy and therapist to remain alive post-therapy (Freed et al., 2010; Pyle, 2006, 2009). Howlett and Guthrie (2001) described TLs acting as a “secure base” for remembering the therapy, providing a physical embodiment of the therapist. Moules (2002, 2009) identified the capacity of TLs to provide an enduring record of clinical work and have the potential to expand clients’ abilities to receive; process; and, actively organise information.

The “Negative Impact” of TLs has also been highlighted. Pyle (2006) described the potential of the tangible nature of the of TLs to trigger rumination and recurrent re-experiencing of negative affective states. Howlett and Guthrie (2001) reported that TLs invoke powerful distressing memories, particularly when participants had found it difficult to engage in, or benefit from, therapy. Similar results have been found in other studies (Hamill et al., 2008; Rayner et al., 2011; Evans & Parry, 1996).

Fusekova (2011) identified that developing exits enabled clients to “open up new perspectives”. Clients described developing new ideas for exits and exit strategies with their therapist which were “common sense” but, at the same time, felt different and “novel” because they could not have generated these without their therapist. Service users described the emergence of a more in-depth understanding of themselves through the process of experimenting with planned exits. Sandhu, Kellet & Holmes (2017) identified the following stages within the revision phase: 1) “Developing an Observing Self” that resulted in clients becoming more self-reflective and aware of their patterns; 2) “Change in Procedures and Roles” whereby clients are able to engage in different roles and procedures; and, 3) “Support and Maintenance of Change”, which was linked to clients referring back to the exits highlighted on the reformulation.

In a review of group CAT, Ruppert (2013) found that “Being in a Group” became a theme in itself, due to the experience of group CAT being clearly distinct from experiences of CAT delivered as an individual therapy. Service users described enjoying meeting new people; learning about themselves and others; and, helping each other. Despite these positives, respondents also felt that one-to-one sessions could have been helpful alongside the group.

References

Balmain, N., Melia, Y., John, C., Dent, H. & Smith, K. (2021). Experiences of receiving cognitive analytic therapy for those with complex secondary care mental health difficulties. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 94, 120 – 136.

Chadwick, P., Williams, C. & Mackenzie, J. (2003). Impact of case formulation in cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(6), 671 – 680.

Corbin, J.M. & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3 – 21.

Evans, M., Kellett, S., Heyland, S., Hall, J. & Majid, S. (2017). Cognitive analytic therapy for bipolar disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(1), 22 – 35.

Evans, J. & Parry, G. (1996). The impact of reformulation in cognitive‐analytic therapy with difficult‐ to‐help clients. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory and Practice, 3(2), 109 – 117.

Freed, P.E., Dorcas, E., McLaughlin, D.E., Smithbattle, L., Leanders, S. & Westhaus, N. (2010). It’s the little things that count: The value in receiving therapeutic letters. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31, 265 – 272.

Fusekova, J. (2011). Mechanisms of Change: A Qualitative Investigation into the Emergence of Exits in Cognitive Analytic Therapy. Doctoral dissertation, Lancaster University.

Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A.L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Aldine, New York.

Hamill, M., Ried, M. & Reynolds, S. (2008). Letters in cognitive analytic therapy: The patient’s

experience. Psychotherapy Research, 18(5), 573 – 583.

Howlett, S. & Guthrie, E. (2001). Use of farewell letters in the context of brief psychodynamic‐ interpersonal therapy with irritable bowel syndrome patients. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 18(1), 52 – 67.

Ingrassia, A. (2003). The use of letters in NHS psychotherapy: A tool to help with engagement, missed sessions and endings. British Journal of Psychotherapy , 19(3), 355 – 366.

Jefferis, S., Fantarrow, Z. & Johnston, L. (2021). The torchlight model of mapping in cognitive analytic therapy (CAT) reformulation: A qualitative investigation. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 94, 137 – 150.

Kellett, S. & Stockton, D. (2021). Treatment of obsessive morbid jealousy with cognitive analytic therapy: A mixed-methods quasi-experimental case study. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 1 – 19.

Llewelyn, S.P. (1988). Psychological therapy as viewed by clients and therapists. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(3), 223 – 237.

Moules, N.J. (2002). Nursing on paper: Therapeutic letters in nursing practice. Nursing Inquiry, 9(2), 104 – 113.

Qualitative Research in CAT Dr Evelyn Gibson Moules, N.J. (2003). Therapy on paper: Therapeutic letters and the tone of relationship. Journal of

Systemic Therapies, 22(1), 33 – 49.

Moules, N.J. (2009). Therapeutic Letters in Nursing: Examining the character and influence of the written word in clinical work with families experiencing illness. Journal of Family Nursing, 15(1), 31 – 49.

Pyle, N.R. (2006). Therapeutic letters in counselling practice: Client and counsellor experiences. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 40(1), 17 – 31.

Pyle, N.R. (2009). Therapeutic letters as relationally responsive practice. Journal of Family Nursing, 15(1), 65 – 82.

Rayner, K. (2005). Clients’ Experience and Understanding of Change Processes in Cognitive Analytic Therapy. DClinPsy Thesis, University of Sheffield.

Rayner, K., Thompson, A.R. & Walsh, S. (2011). Clients’ experience of the process of change in cognitive analytic therapy. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 84(3), 299 – 313.

Ruppert, M. (2013). Group Therapy Integrated with CAT: Interactive Group Therapy Integrated with Cognitive Analytic Therapy, Understandings and Tools (Doctoral dissertation, University of East Anglia.

Sandhu, S.K., Kellett, S. & Hardy, G. (2017). The development of a change model of “exits” during cognitive analytic therapy for the treatment of depression. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 24(6), 1263 – 1272.

Saunders, S.M. (1999). Clients’ assessment of the affective environment of the psychotherapy session: Relationship to session quality and treatment effectiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55(5), 597 – 605.

Shine, L. & Westacott, M. (2010). Reformulation in cognitive analytic therapy: Effects on the working alliance and the client’s perspective on change. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 83(2), 161 – 177.

Stockton, C. (2012). The Efficacy of Narrative Reformulation of Depression in Cognitive Analytic Therapy: A Deconstruction Trial. Doctoral dissertation, University of Sheffield.

Taplin, K. (2015). Service User Experiences of The Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation (SDR) in Cognitive Analytical Therapy (CAT): An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Doctoral Thesis. University of Liverpool.

Taylor, P.J., Perry, A., Hutton, P., Tan, R., Fisher, N., Focone, C., … & Seddon, C. (2019). Cognitive analytic therapy for psychosis: A case series. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 92(3), 359 – 378.

Tyrer, R. & Masterson, C. (2019). Clients’ experience of change: An exploration of the influence of reformulation tools in cognitive analytic therapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 26(2), 167 – 174.